| The exhibition "Mythologies

of the Book. Contemporary Greek Artists" aims to present the entire spectrum

of the contribution of Greek artists to book production. The first part

of the exhibition includes a series of representative publications which

epitomise certain periods, promoted some special traits or served as models

within the relatively short history of modern Greek illustrated editions.

The important books

illustrated by Greek artists from 1900 to 1950 –the period included in

the first part– are certainly a lot more. These editions were selected

in such a way as to demonstrate the principles, underline the continuity

and showcase some landmark editions from that era.

There is no parallel

in Greek art of the European tradition of illustrated books, unbroken from

the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages to the current electronic

publications. Historical circumstances led to the Greek centres’ isolation

from the cities of Europe. Such publications were only addressed to Church

circles and the small expatriate communities in Central European cities.

Unable to keep up

with the proliferation of illustrated books in Europe during the 18th and

19th centuries, Greece only makes its debut in this field in the early

20th century, at first timidly and then experimentally adopting various

illustration techniques. Not surprisingly, the early attempts are influenced

by the widely accepted aesthetics of Symbolism and the traditional notion

of books of the late 19th century rather than the radical trends of that

time which shaped book aesthetics in the 20th century.

In Paris the illustrated

editions

de luxe –printed on quality paper with more than one suites, mostly

etchings– had already appeared since 1880, with the collectible

livres

d`artistes following in the first years of the 20th century. These

editions combined the work of painters with the visions of ambitious art

publishers like D.H. Kahnweiler and A. Vollard, introducing a subversive

aesthetic not always acceptable to bibliophiles, who turned to more traditional

forms of illustration.

In Greece such editions

arrive in the early 1920s, coming from foreign publishers or from the artists

who illustrated them; they appear only occasionally and are addressed mainly

to book collectors. It is more than a decade later that Athens-based publishers

begin to commission artists –engravers, mostly– to illustrate albums published

in very limited numbers.

Yannis

Kefalinos

Shine

and fall silent, 1951 |

|

|

Yannis

Kefalinos

Anatole

France, Sur la Pierre blanche, 1924 |

|

| Dimitrios Galanis,

Lycourgos

Kogevinas and Yannis Kefalinos are three Greek artists who lived

in Paris since the beginning of the century and got to know the interests

of French bibliophiles. They turned to illustrating books and worked with

French publishers for the production of mostly common editions; in order

to publish an album with a content of particular interest to them, they

would often finance the production themselves.

Galanis became a

naturalised French from early on and lived in Paris to the end of his life.

He made the personal acquaintance of Derain, Maillol and Matisse and got

to know their illustration work. For his own work he embraced the aesthetic

of Maillol rather than the innovative techniques and the fauvist aesthetic

of Matisse. The compositions he favoured were associated mostly with traditional

illustration and expressed through elaborate headpieces and tailpieces,

impressive initial caps, full-page frontispieces and full-page narrative

pictures in editions that were painstakingly executed as a whole (Carmen,

Nourritures Terrestres, Terre Natale). He produces etchings

and manière noire engravings and more rarely end grain woodcuts

(Oedipus the King). His album Histoire Naturelle is considered

to be of unsurpassed aesthetic and is included among the most accomplished

illustrations of similar texts, along with J. Renard’s

Histoires Naturelles

with illustrations by H. Toulouse-Lautrec (1899) and P. Picasso’s Histoire

Naturelle (1942) again by Buffon. It is worth noting that Galanis did

not illustrate texts by Greek writers, and it was only in very few cases

that he was inspired by classics (Idylles de Theocrite).

Dimitrios

Galanis

André

Gide, Les Nourritures Terrestres, 1930 |

|

|

Lycourgos

Kogevinas

Marie

Aspiotis & René Puaux, Corfu, 1930 |

On the contrary, the

painter and engraver Lycourgos Kogevinas opted for themes which promoted

the historical Greek landscape and combined them with texts on Greece written

by French scholars in editions with superbly executed and detailed etchings

(Grèce Paysages antiques, Le Mont Athos, Corfu etc).

During the period

he lived in Paris Yannis Kefalinos illustrated French literary texts (Sur

la Pierre blanche), but mostly he studied the aesthetics of books and

was subsequently led to design a new Greek font. Upon his return to Greece

he edited two magnificent editions. In the album Ten White Lecythi in

the Athens Museum the superimposed impressions of different printing

techniques on the same page (burin engraving, etching, aquatint and coloured

woodcut) faithfully reproduce the feel of the delicate compositions on

these ancient Attican vessels, in an edition of unique aesthetic value

which successfully reproduces the lost atmosphere of classical painting.

The

Peacock, a pioneering educational album with unusual diagonal compositions,

continuous colour surfaces and clear forms, remains to this day a perfect

example of lucid writing and austere illustration.

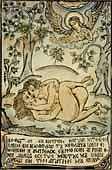

|

Efthymios

Papadimitriou, Solomon, Song of Songs, 1938 |

After the mid-1930s,

illustrated publications and limited editions of albums, mostly with woodcuts,

are produced in Athens and find a steadily responsive public. However,

the time when this form of art saw an unprecedented growth was the war

years (1940-1945). The need to communicate, the lack of painting materials

and the urge to protest made most Greek artists turn towards all kinds

of publications. Some engraved works to illustrate hand-written texts (From

within the walls), while others formed clandestine groups, engraved

and printed small woodcuts and distributed them in albums (The Shrine

of Freedom). In the material collected from those years one can trace

the hidden potential of many artists who became heavily engaged in book

illustration but only during that specific period.

The 1950s was a period

when illustrated books flourished more than any other time in Greece. Large

albums were published, using coloured woodcuts for the most part and illustrating

texts of the ancient and historic literature and, to a lesser extent, contemporary

literary works. The austere images point to influences from ancient and

Byzantine imagery and, selectively, from the contemporary European trends.

Taken as a whole,

the Greek editions illustrated with original prints managed to create a

tradition within a few decades and become known to a wider public. There

is no doubt that the combination of printmaking and books allows the expansion

of the text through visual elements which become definitive means of "visual

communication".

Irene

Orati

|